Rebinding a manuscript is not something to be undertaken lightly. Detailed discussions between the Curator and Conservator in the Department of Manuscripts and Printed Books at the Fitzwilliam were vitally important in coming to the eventual decision to rebind MS 251.

Although rebinding is admittedly a radical decision, we felt that the damage and restricted access that the common and inappropriate eighteenth-century binding continued to cause, combined with the enormous significance of the manuscript within, merited this approach. The eighteenth-century binding would be recorded and preserved in the box with the newly bound manuscript.

Removal of the old binding would then allow the leaves to be conserved and bound in a structure inspired by bindings of the period in which the manuscript was produced.

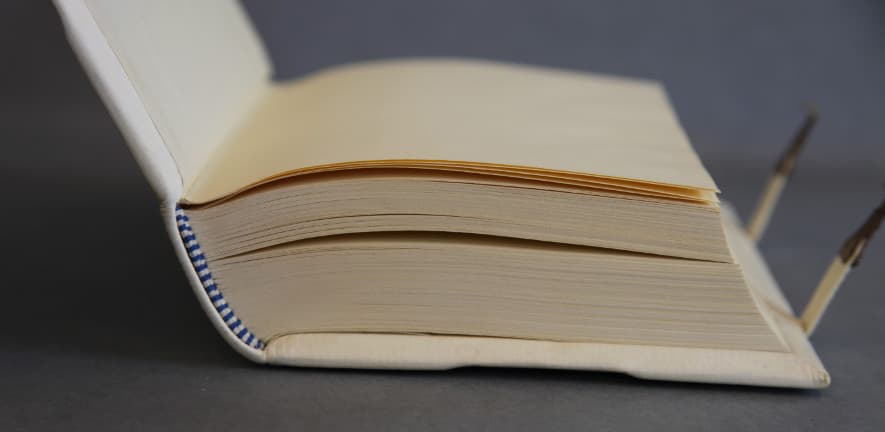

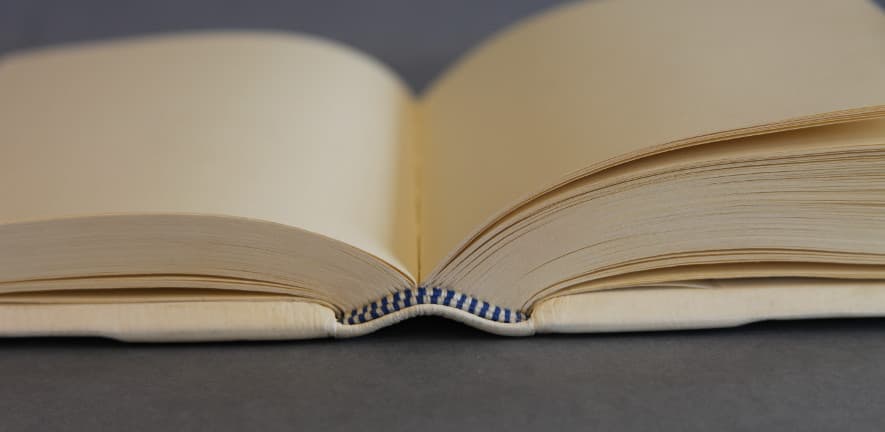

Such Gothic bindings are notable for the free opening of the leaves they contain. A Gothic style of binding is designed precisely to flex into an arch when the book is opened, allowing the leaves to open flat from the spinefold.

By contrast, the eighteenth-century binding was glued and lined heavily on the spine to prevent the spine from flexing thereby protecting inadequate sewing and the gold tooling on the spine from being damaged.

The only place at which the book opened from the spine fold was at the point where the inflexible spine-lining had split. The sewing supports were already showing signs of wear at this point as a result.

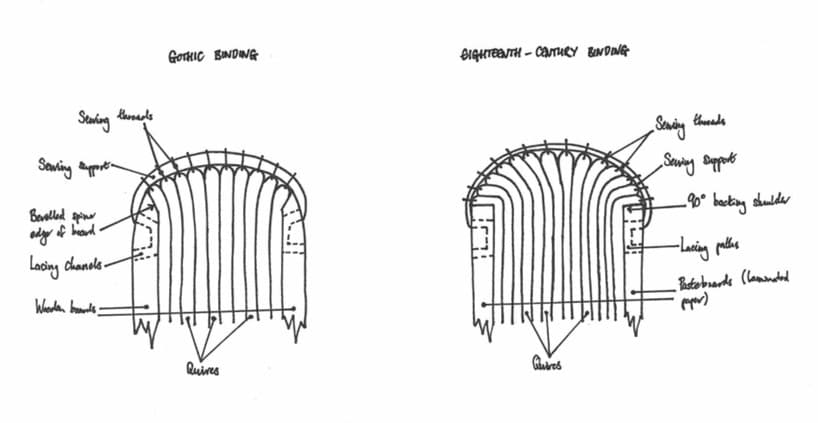

Gothic and modern spine shapes

Gothic and eighteenth-century binding structures both have round spines, but the mechanics of the ways in which they open is very different due to the contrast in the say the spine shape is produced. The round shape of the Gothic structure is a product of the swell of the sewing thread and the lacing on of the bevelled boards. The eighteenth-century spine is achieved by hammering the book and making 90-degree backing shoulders to accept the boards. Where the Gothic spine is designed to flex into a supportive arch, the eighteenth-century spine is glued and lined precisely so that it does not flex and therefore makes a firm surface on which to apply decorative gold tooling.

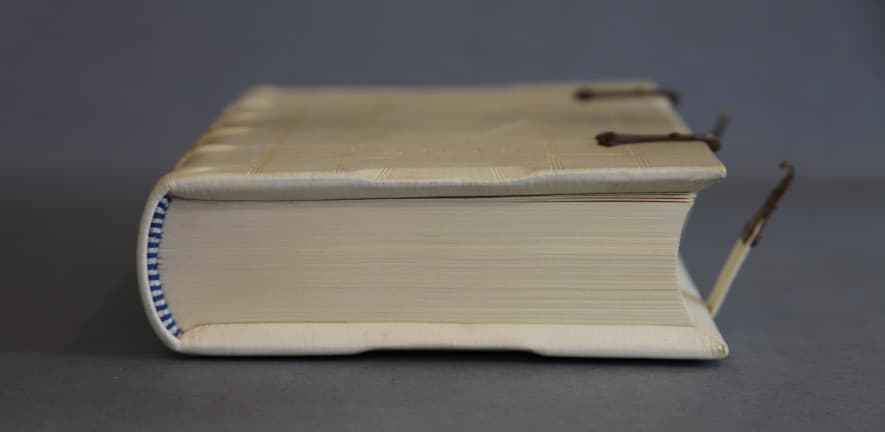

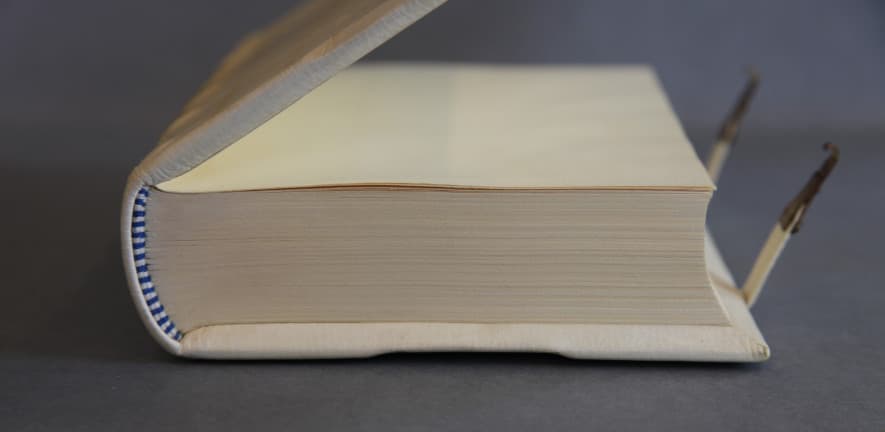

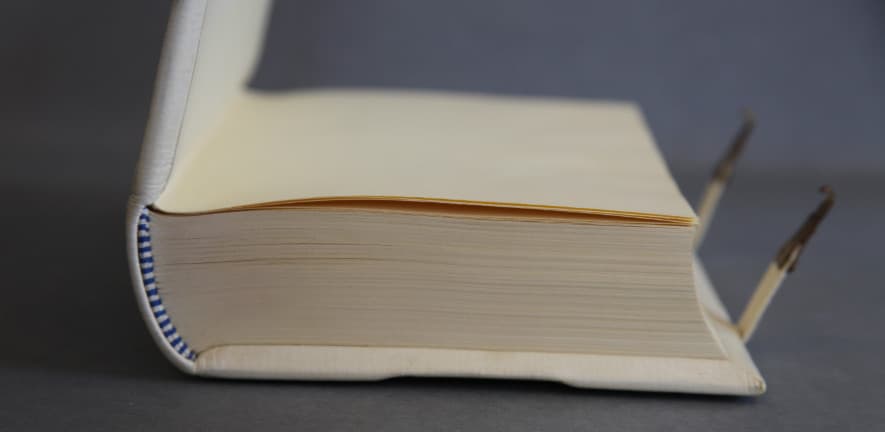

The opening characteristics of a Gothic binding structure and an eighteenth-century-style binding.