The affective power of medieval and Renaissance images rested largely in the artists’ ability to paint lifelike faces. As Christian prayers centred upon the bodies of Christ and the saints, painting their flesh was an act of devotion imbued with mystery – as if bringing them to life. Physiognomy and medicine also influenced artistic practice. Flesh colours were considered indicators of character, determined by the balance of the four elements (earth, air, fire, water) and their qualities (hot, cold, dry, wet) in the human body.

To paint convincing flesh tones, illuminators employed a variety of pigments and techniques. Using the bare parchment (made of animal skin) was the most economical. The most sophisticated method involved the application of complex mixtures in multiple layers to animate figures, suggest character and distinguish the living from the dead.

Martyrdom of St Stephen

Initial S from an Antiphoner

Italy, Bologna, c.1300-1320

ARTIST: Nerio (active c.1300-1320)

Involved in the ambitious pictorial programmes of multi-volume Choir books, the innovative and prolific Bolognese artist Nerio developed an efficient method of painting the flesh. He applied a glossy, enamel-like, pink colour over a green base, leaving parts of the base visible as areas of shadow. A few deft brush strokes sketched in facial features. Small red or brown daubs lent colouristic definition. This simple technique involved surprisingly complex mixtures. The green base contains six pigments: lead white, azurite blue, indigo, green or red earth, and massicot (lead oxide yellow). The pink layer has vermilion and lead white bound in gum Arabic.

Cat. 77 - Fitzwilliam Museum, Marlay cutting It. 80c

Bequeathed by Charles Brinsley Marlay in 1912

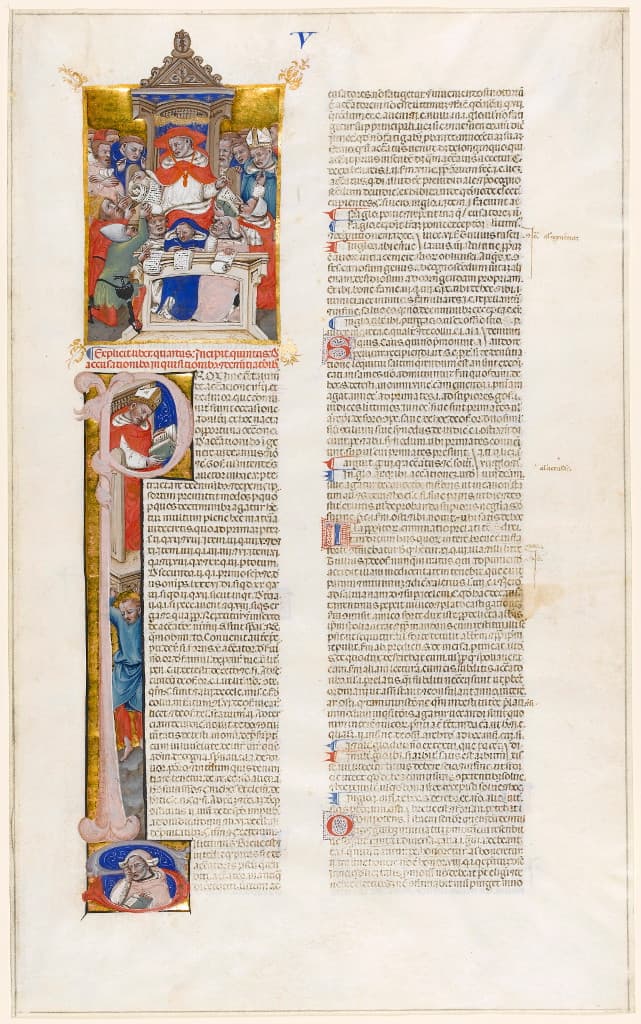

Cardinal-judge conducting a court hearing

Leaf from Iohannes Andreae, Novella in Decretales

Italy, Bologna, c.1365

SCRIBE: Bartolomeo dei Bartoli

ARTIST: Nicolò di Giacomo di Nascimbene (documented 1349-1403)

The leading 14th-century Bolognese illuminator Nicolò da Bologna created animated figures with finely chiselled, expressive faces. His flesh-painting technique differs from that of his Bolognese predecessors and Tuscan contemporaries. Instead of a green base, Nicolò used a grey-brown underlayer (a mixture of lead white, iron gall ink, azurite and vermilion) with vermilion red brush strokes over it. He drew facial features in brown and then covered the red and brown strokes with a transparent white glaze, producing a smooth flesh tone. He added lead white highlights. This technique became the hallmark of 14th-century Bolognese illumination.

Cat. 79 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 331

Purchased by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1932

Dormition of the Virgin

Initial G from a Gradual

Italy, Venice, c.1420

ARTIST: Master of the Murano Gradual (active c.1420-1460)

This initial comes from a Choir book illuminated on the Venetian island of Murano by an artist experimenting with styles and materials. His blues combine imported ultramarine with local smalt, borrowed from Murano’s thriving glass industry. He painted expressive faces of tactile plasticity, starting with a pink base (a mixture of vermillion, red lead, red earth and lead white) and modelling shadows with a thin vermilion wash. These layers lend the faces a sun-kissed appearance, while highlights of diluted lead white add luminosity. Strokes and daubs of thick, opaque lead white add texture to eyebrows and hair.

Cat. 81 - Fitzwilliam Museum, Marlay cutting It. 18

Bequeathed by Charles Brinsley Marlay in 1912

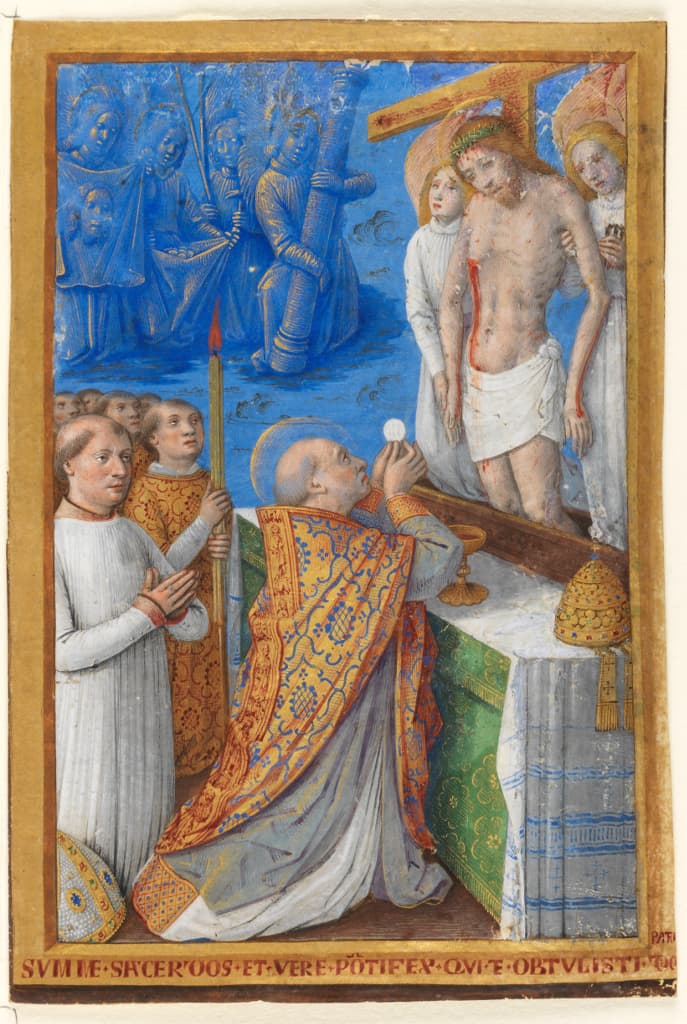

The Mass of St Gregory

Leaf from the Hours of Charles de Martigny

France, Tours, c.1485-1494

ARTIST: Jean Bourdichon (1457-1521)

The royal painter and illuminator Jean Bourdichon created an intense devotional experience for the manuscript’s owner, Bishop Charles de Martigny, by including him in St Gregory’s vision of Christ. Charles’ image (left) and the swollen, tear-heavy eyes of Christ’s attendants showcase Bourdichon’s exceptional talent as a portraitist. He modelled the pale orange base of the bishop’s face with a dense network of fine stipples and hatching strokes in multiple tonalities of tan, brown, pink, red, orange, white, black, grey and blue. The complex mixtures and painting technique conjure up the patron’s ‘living’ presence.

Cat. 87 - Fitzwilliam Museum, Marlay cutting Fr. 6

Bequeathed by Charles Brinsley Marlay in 1912

Crucifixion

Miniature from the Hours of Albrecht of Brandenburg

Flanders, Bruges, 1522-1523

ARTIST: Simon Bening (1483-1561)

This miniature, along with five more at the Fitzwilliam Museum and many others now dispersed across the world, once embellished a sumptuous Book of Hours. It was made for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545), Archbishop-Elector of Mainz and a discerning art collector. He commissioned the manuscript from Simon Bening, the Flemish artist described at the time as ‘the greatest master of the art of illumination in all of Europe.’

This image includes the two thieves who were crucified with Christ. The good thief on Christ’s right (our left), lifts his head up in the hope of salvation. The thief on Christ’s left (our right) turns away and looks down, having scorned the Saviour. The flesh tones vary accordingly. Christ’s body, pale and chalky, is painted with lead white and modelled with brown ochre and azurite blue in the grey shadows. The good thief is painted in similar hues, while the bad thief is rendered with a mixture rich in yellow and brown ochres, his jaundiced flesh embodying his betrayal.

Cat. 89a - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 294a

Purchased by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1918

www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated