By combining art-historical and scientific analyses of illuminations, we can trace the creative process from the artists’ original concepts, through their choice of materials to the finished masterpieces. Non-invasive methods can identify pigments and detect sketches beneath the surface without the need to remove samples. They reveal artistic practices and secrets.

Scientific analyses also discredit long-held misconceptions, including the myths that illuminators used pigments in their pure form, and that they bound them in gum (resin) or glair (beaten egg white), but not in egg yolk, which was reserved for panel paintings. In fact, illuminators employed increasingly complex mixtures of pigments from the 11th century onwards, and used egg yolk selectively alongside gum and glair. There was no rigid distinction between panel painting and manuscript illumination, since many artists worked in both media.

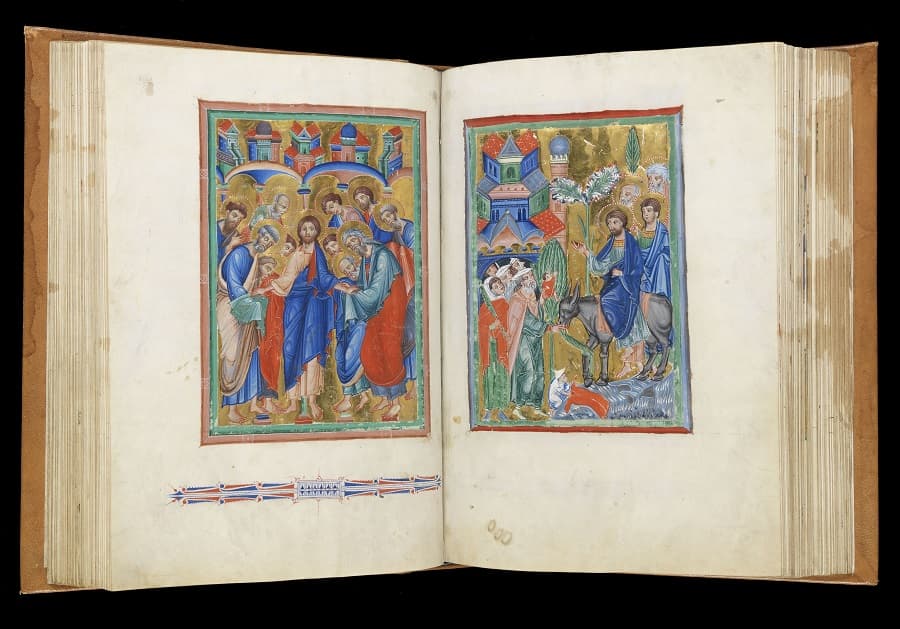

Christ with Apostles and Entry into Jerusalem Psalter Silesia, Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), c.1255-1267

Commissioned by a Duchess of Breslau, this Psalter was produced by Silesian scribes and illuminators, with the brief, but brilliant guest-appearance of a Paduan artist. He brought north of the Alps an Italo-Byzantine style, represented by the image on the left. The image on the right exemplifies the local tradition. The two miniatures also differ in materials – azurite, the blue of choice on the left, is absent from the image on the right which contains indigo and ultramarine instead. The numerous artists recruited to complete this ambitious manuscript exchanged some stylistic features, but rarely shared materials.

Cat. 26 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 36-1950, fols. 49v-50r

Bequeathed by Thomas H. Riches in 1935, received in 1950

Pentecost with patron’s portrait and arms Missal Italy, Florence, 1402-1405

This Missal preserves the portrait and arms of its patron, Angelo Acciaiuoli (1340-1408), a Florentine patrician and Roman Cardinal – seen here in his vermilion red robes. Four artists worked on the volume in 1402-1405: Bartolomeo di Fruosino, Bastiano di Niccolò di Monte, Matteo di Filippo Torelli and his brother Bartolomeo di Filippo Torelli. Acciaiuoli paid them over 32 golden florins – the equivalent of around £30,000 today. They collaborated closely, sharing materials and techniques. Trained as panel painters, they created the figures with pigments bound in egg yolk. The foliage was left to assistants who did not use egg yolk to bind their pigments.

Cat. 28 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 30, fol. 148r Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816

Virgin and Child; The Hours of Isabella Stuart; France, Angers, c.1431{: .text-info }

Cradled within a crescent moon, the Virgin and Child are accompanied by Saints Peter and Paul, the Trinity and angels descending from heaven. The luminous pigments – ultramarine, vermilion, red lead, malachite and an organic pink – and the three-dimensional modelling of the drapery create an illusion of palpable presence. The artist painted freehand, without preparatory sketches, unlike his collaborators who used extensive underdrawing in their contributions to the volume. Probably commissioned c.1431 by Yolande of Aragon, Duchess of Anjou, for her daughter’s wedding to Francis I of Brittany, the manuscript was adapted c.1442 for Francis’ second wife, Isabella Stuart.

Cat. 30 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 62, fol. 136v

Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816