Not all medieval illuminators were monks. Nuns, friars and the clergy in cathedrals and parish churches – as well as monks – played a vital role in manuscript production throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. By the 12th century lay professionals were travelling in search of commissions from both secular patrons and religious communities. In the 1200s, they settled in major cities and university towns, establishing thriving commercial networks that would lay the foundations for the early modern book trade.

Medieval illuminators are less anonymous and invisible than we might think. Some left both their names and images, often shown in prayer. From the 12th century onwards, a few depicted themselves at work. By the 1400s illuminators are shown surrounded by tools and pigments. The presence of associates, including women, reflects the collaborative and familial nature of manuscript production.

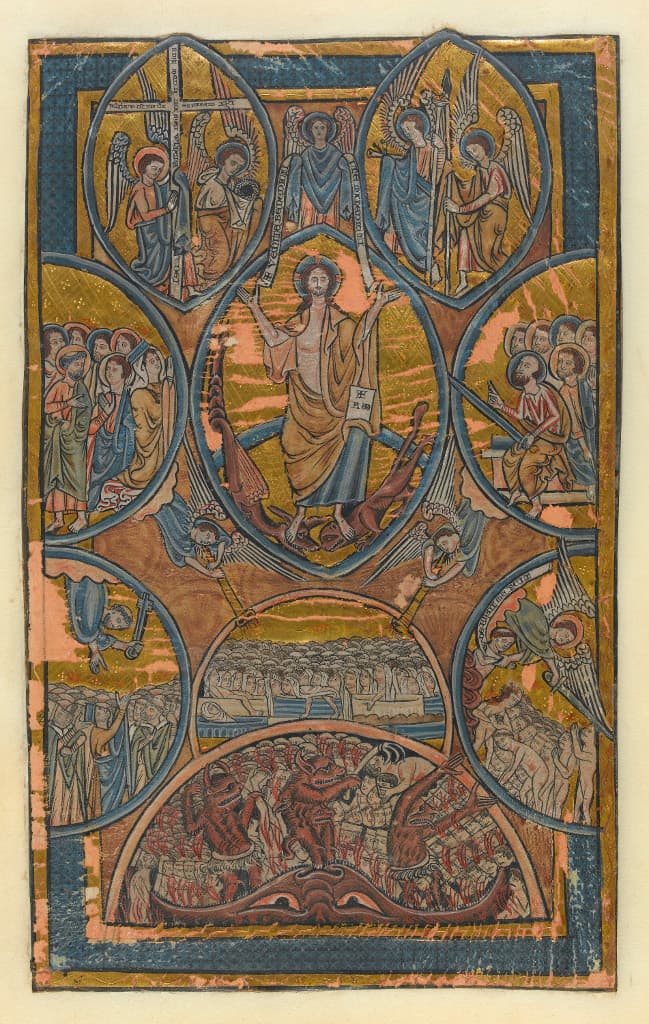

Last Judgement

Miniature from a Psalter England, Oxford, c.1230-1250

ARTIST: William de Brailes (documented c.1230-1260)

Depictions of illuminators are rare, but the prolific artist William de Brailes, based in 13th-century Oxford, left at least three images of himself. Here he is shown in the lower right semi-circle, being saved on Judgement Day. St Michael lifts him away from the sinners who are condemned to eternity in Hell. William holds a scroll inscribed ‘W[illiam] de Braile[s] made me.’ It confirms his identity, advertises his authorship of the image and reveals the spiritual anxieties of a highly successful member of the professional book trade.

Cat. 17 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 330.iii

Purchased through the National Art Collections Fund in 1932