Medieval optics, or Perspectiva, emerged in the 13th century from earlier theories of light and vision. Optical studies of geometry and colour informed artistic practices. Perspectiva’s proponents held that the shape and colour of objects was transmitted to our eyes by a pyramid of visual rays. This pyramid would become the tool of linear perspective, advocated in Alberti’s treatise On painting (1435). 13th-century scholars revised ancient colour theories. They removed white and black from the chromatic scale whose seven main colours, they argued, could be mixed into an infinite range of hues.

These advances coincided with developments in painting, best observed in illuminated manuscripts. By c.1300, illuminators were creating three-dimensional images with a sense of spatial depth. A century later, they were simulating atmospheric effects and optical illusions, including mirror reflections and the fleeting colours of peacock feathers.

Dedication of the Temple of Solomon Miniature from the Egmond Breviary

Northern Netherlands, Utrecht, c.1435-1440

Artist: one of the Masters of Zweder van Culemborg (active c.1415-1445)

This image belonged to a manuscript made in Utrecht for a member of the ruling family of Guelders-Jülich, probably Duke Arnold of Egmond. It shows Solomon praying in his newly-built Temple in Jerusalem. Linear perspective unites the tiled floor, columns and vaulted ceiling into a convincing three-dimensional space. Its central axis, linking Solomon, the scroll of the Torah on the altar, the statue above and the window, leads the eye across the depth of the building. The archway, while positioning the observer outside the sacred space, offers a privileged view of the solemn celebration.

Cat. 90 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 1-1960 Given by Francis Wormald in 1960

King David, Initial B from an Antiphoner Italy, Bologna or Rome, c.1490-1500

A penitent David kneels in a palatial courtyard. An extraordinarily varied palette is employed to simulate surfaces and textures, from the marble columns to the bejewelled robes, and to conjure up spatial depth. The path behind the fence and the loggia leads the eye across the river, past the gondola, to the city, through the archway, onto the hills and up to the castle. From there a magnificent vista opens over valleys and mountains stretching to the horizon. The sophisticated use of colour, consistent light source, linear and aerial perspective creates a coherent and expansive pictorial space.

Cat. 97 - Fitzwilliam Museum, Marlay cutting It. 25 Bequeathed by Charles Brinsley Marlay in 1912

Betrayal and Arrest of Christ, Leaf from the Hours of Charles de Martigny

France, Tours, c.1485-1494

Artist: Jean Bourdichon (1457-1521) and workshop

This leaf belonged to a Book of Hours illuminated for Bishop Charles de Martigny by the royal painter and illuminator Jean Bourdichon. He conveyed the drama of Christ’s arrest by contrasting deep night shadows with highlights executed in varying concentrations of shell gold. Beneath a starry sky, blazing torches illuminate armour, clothing, hair and flesh. Bourdichon’s skilful simulation of reflected light draws the viewer’s attention to important details of the pictorial narrative, notably the money bag that Judas clutches as he betrays Christ with a kiss.

Cat. 102 - Fitzwilliam Museum, Marlay cutting Fr. 4 Bequeathed by Charles Brinsley Marlay in 1912

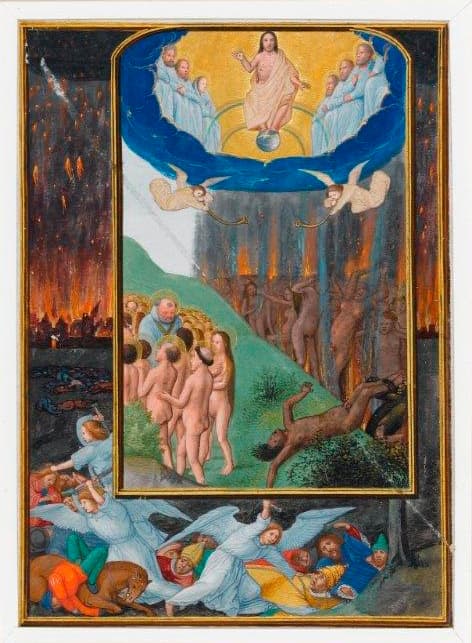

Last Judgement, Miniature from the Hours of Albrecht of Brandenburg

Flanders, Bruges, 1522-1523

Artist: Simon Bening (1483-1561)

These images, three more at the Fitzwilliam Museum (two displayed in section 13) and many others now dispersed across the world, belonged to the Hours of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg (1490-1545), Primate of Germany, friend of Erasmus, and patron of Dürer, Cranach and Grünewald. The manuscript was painted by Simon Bening, the most sought-after Flemish illuminator of the 16th-century. His compositions include motifs and pictorial strategies that reveal knowledge of works by eminent painters, illuminators and printmakers, including Jan van Eyck, the Vienna Master of Mary of Burgundy, Gerard David, Schongauer and Dürer.

Bening reserved the most dramatic treatment of light and the most sophisticated use of colour for the fires of Hell. In the main image, red lead, indigo, azurite, lead white, copper green, carbon black, lead-tin yellow and yellow ochre are accentuated with sparks of shell gold. An organic dye creates the purple flames in the side borders, while lead-tin yellow provides flashes of infernal light. Figures in the lower border derive from Dürer’s Apocalypse-inspired woodcut, The Massacre by the Four Angels. Bening reminded his patron that all sinners, even high-ranking ecclesiastics, would be punished at the end of time.

Cat. 105c - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 294d

Purchased by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1918

www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated

Guardian Angel with a mirror-image of death; Book of Hours

Flanders, Bruges, c.1460-1470

Standing over an open grave, an Angel holds a mirror with a skull that stares at the viewer – a reflection of their future state. A metaphor for vanity, the mirror here invites self-examination. Introducing a prayer to the Guardian Angel, the image underscores the medieval preoccupation with death’s ever-present threat. The wall and window reflected in the mirror are tangible components of the viewer’s own space. The skull too breaches the boundaries between painting and reality: as it casts shadows on the wall and reflects the daylight streaming through the window, it becomes part of the here and now.

Cat. 106 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 53, fol. 6v Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816

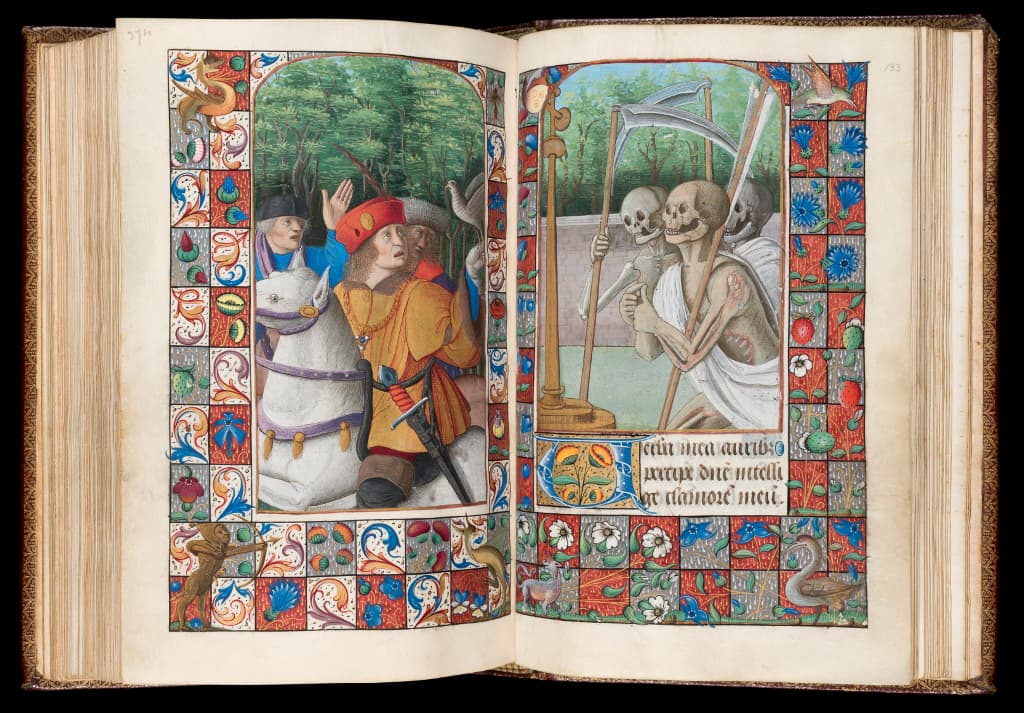

The Three Living and the Three Dead

Book of Hours

Western France, c.1490-1510

Three noblemen enjoying a hunt on a fine summer day are suddenly confronted by three hideous skeletons who proclaim:

‘You are what we were and we are what you will become.’ Usually presented as a single scene, this image was a favourite frontispiece to the Office of the Dead in Books of Hours, alongside mirror-reflections of skulls grinning at the viewer. Here, the riders and skeletons mirror each other across the page. The chilling anticipation of their physical contact, face to face, when the book is closed is a constant reminder of death, ever-present and undiscriminating.

Cat. 107 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 92, fols. 132v-133r Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816