Colour was part of every discourse and discipline, from natural history and medicine to theology. Context was crucial; a specific hue could convey multiple messages. Green signalled new life, Eden and Paradise. Red evoked a lover’s lips, Christ’s wounds, the flames of hell and the power of the Holy Spirit. White denoted truth, purity and perfection, but was also associated with death. Blue, linked to the divine, could also stand for the unusual and potentially dangerous.

Colour was a marker of difference and distinction. Its monetary and symbolic values reflected social hierarchies and moral norms. Garments of particular shades – whether monastic habits, royal robes, jesters’ costumes or lawyers’ gowns – indicated status, occupation, and religious or political affiliations. Colour influenced how individuals were perceived by others, but also expressed personal beliefs and aspirations.

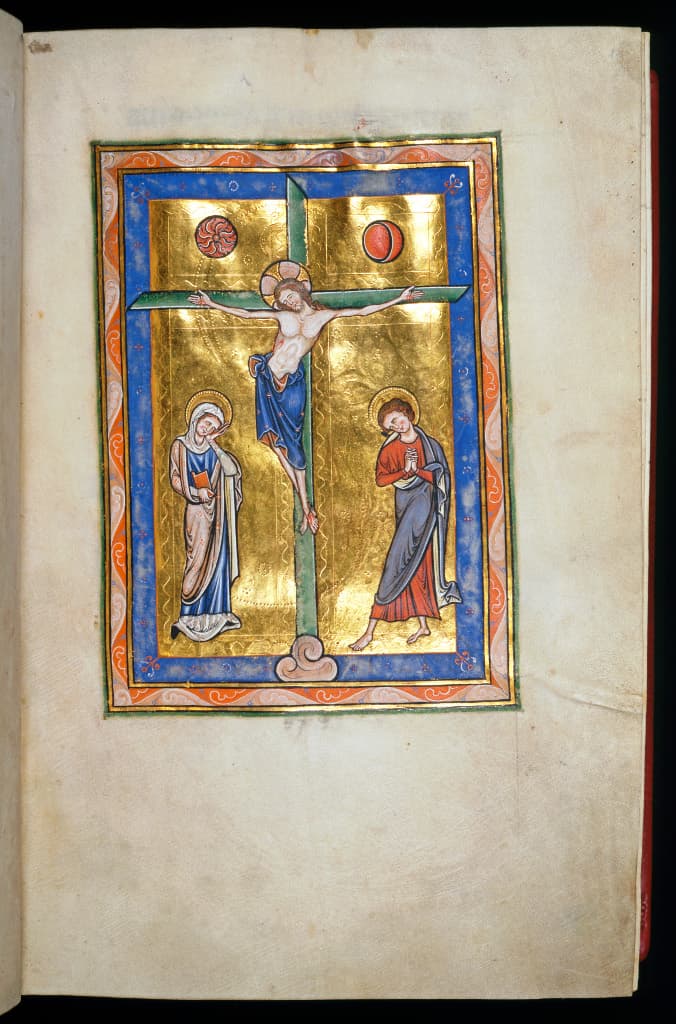

Crucifixion; The Peterborough Psalter; England, Peterborough, c.1220-1225

A variety of pigments, including locally sourced organic yellows and imported ultramarine, were used throughout this elegant volume. Green made from verdigris was reserved for one area: the Cross. Green Crosses are found in Crucifixion scenes from the 11th century onwards. Artists used the colour to link the Cross with the Tree of Life in Eden, a symbol of eternal life. According to Christian theology, Christ’s death and resurrection offered redemption and immortality to humanity.

Cat. 109 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 12, fol. 12r

Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816

www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated

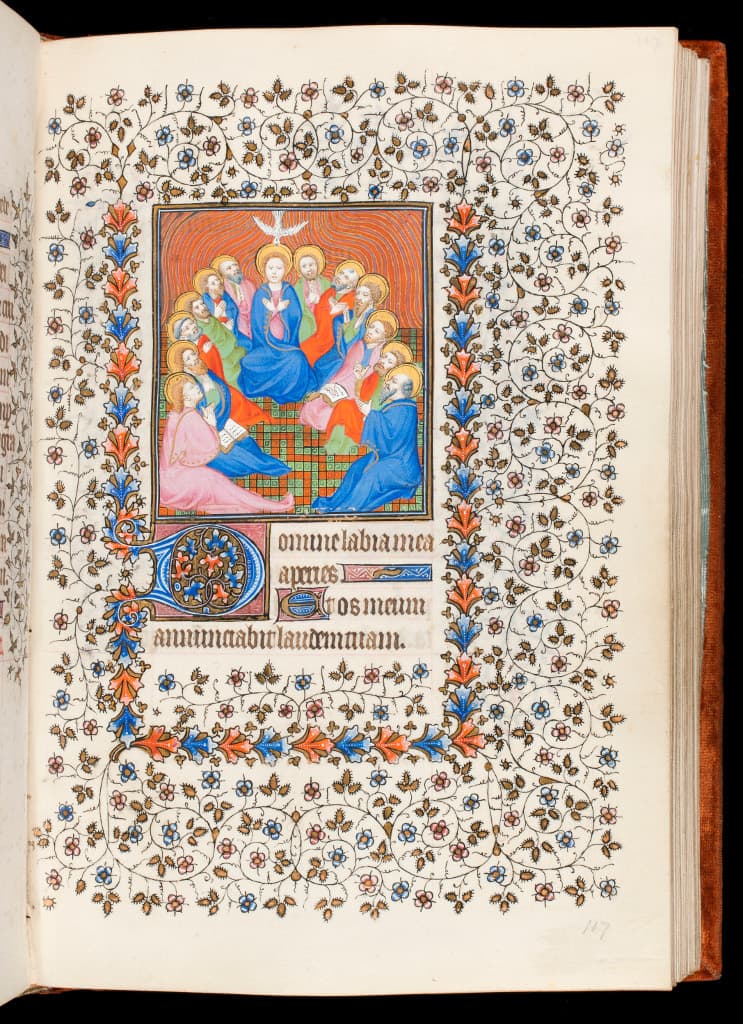

Pentecost

Book of Hours

France, Paris, 1410-1412

ARTIST: Luçon Master (documented 1401-1417)

According to the Bible, when Christ’s disciples gathered to celebrate Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descended upon them with ‘tongues of fire’ from heaven. Instantly, they could understand and speak foreign languages, which allowed them to spread Christ’s message throughout the world. Medieval artists often used gold or red rays to symbolise divine energy transferred from heaven to earth. Here, the power of the Holy Spirit is expressed by waves of alternating colours instead. The dramatic background is an ingenious artistic interpretation of the miraculous ‘tongues of fire’ that rained down from heaven.

Cat. 114 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS McClean 80, fol. 117r

Bequeathed by Frank McClean in 1904

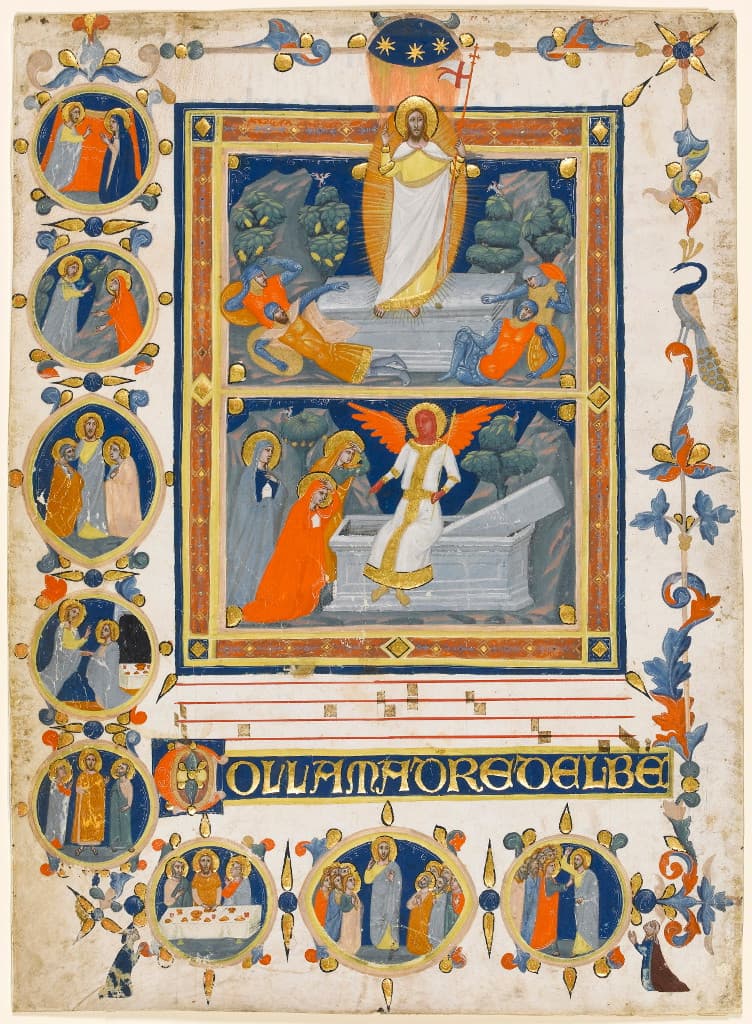

Resurrection

Leaf from a Laudario

Italy, Florence, c.1330-1340

ARTIST: Pacino di Bonaguida (documented 1303-1330)

This leaf belonged to a songbook commissioned by a Florentine confraternity whose members, shown in the lower border, would gather to chant hymns. The Easter hymn starts beneath the image. The dark blue sky contrasts with Christ’s yellow robe, the angel’s orange-red wings and the gleaming haloes. Costly vermilion was used only for the cross on Christ’s banner, and the angel’s face and hands. According to Matthew’s Gospel, the angel had a face ‘like lightning’, which the eminent Florentine painter and illuminator Pacino di Bonaguida conveyed in the glowing red complexion.

Cat. 115 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 194

Purchased in 1891

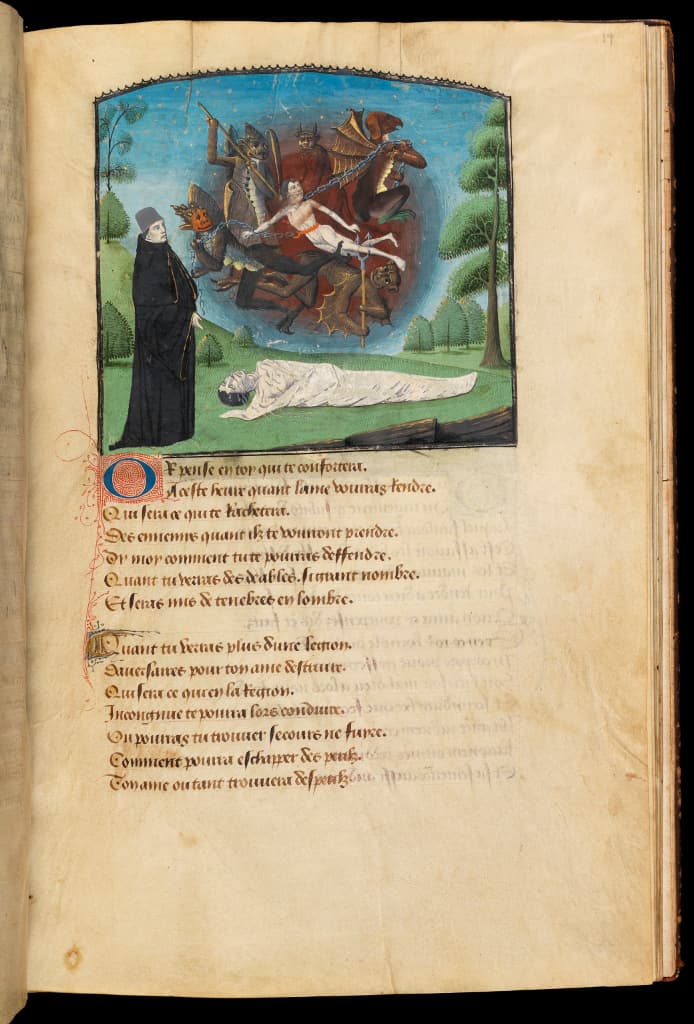

The Soul assaulted by demons

Jean de Castel, Le Specule des pecheurs

Northern France, c.1470-1480

The striking images in this ‘Mirror of Sinners’, a poem on death and damnation, exploit the multiple meanings of colours. Crawling with maggots, a corpse lies on the ground, cocooned in a white shroud. Standing nearby is the author of the text, dressed in a black robe. Here, white signals death and decay, while black is a sign of learning and authority. Having left the body, the airborne Soul represented by a naked figure is assaulted by demons. The Soul’s pale flesh stands out against the blood-red cloud, a portent of the fiery depths of Hell.

Cat. 121 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 164, fol. 19r

Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816

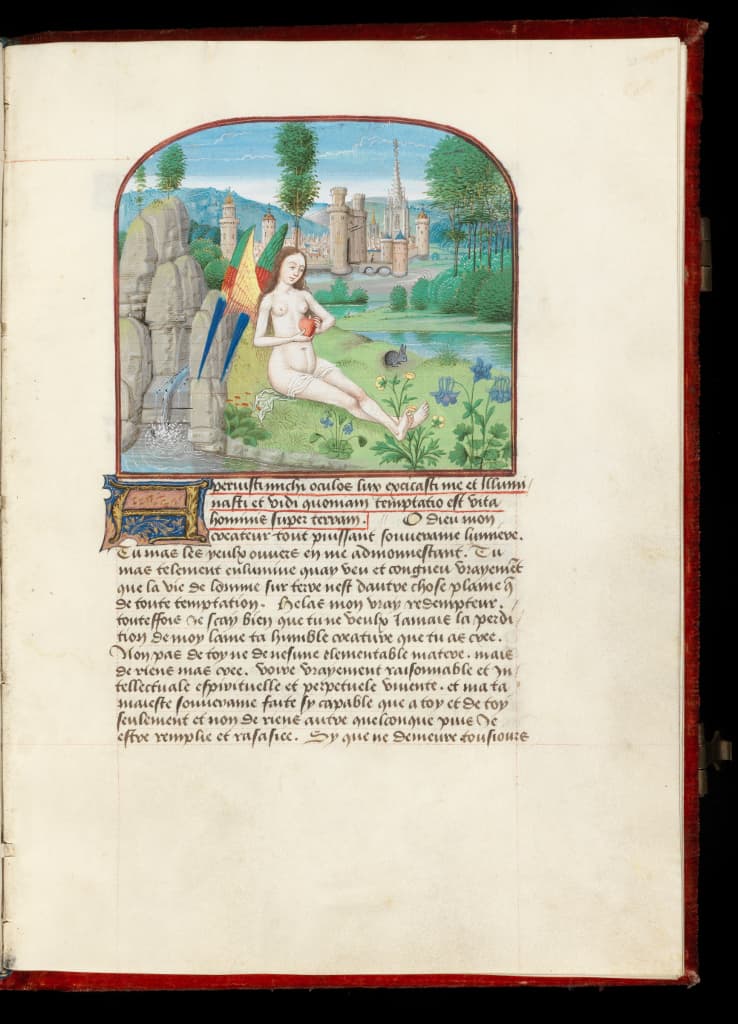

The Soul holding her heart

René of Anjou, Le Mortifiement de vaine plaisance

Flanders, Hesdin, c.1470-1475

ARTIST: Loyset Liédet (c.1420-1479)

Composed by the famous ruler, author, and art patron, René of Anjou, this religious treatise describes a conflict between the devout Soul and the sinful, rebellious Heart. The Soul, represented by a winged female figure, clasps her plump, red heart in her hands. The Heart is shown as the familiar red symbol, first employed by western artists in the 14th century and still recognized worldwide.

Cat. 122 - Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 165, fol. 31r

Bequeathed by Viscount Fitzwilliam in 1816